RUG GUIDE

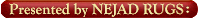

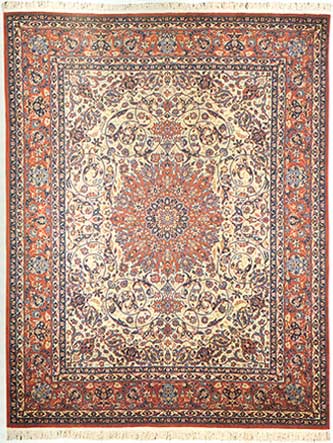

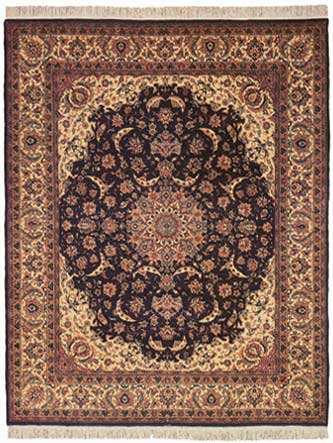

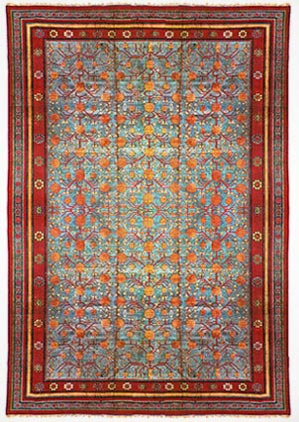

THE ILLUSTRATED RUG - PART 2RUGS OF THE NEAR AND FAR EASTINDIA Carpet weaving was introduced to India during the 16th century following the Mogul conquest of Akbar the Great. Influenced by Persian culture, this Moslem dynasty established carpet factories which produced Persian-inspired weavings as well as classic Mogul carpets featuring realistic floral and pictorial renditions. For centuries, India created among the most exquisite carpets in history, mainly in Jaipur, Kashmir, Agra, and Benares. Today, many of them are guarded museum masterpieces. With the decline of the Mogul empire and the corresponding rise of the British empire during the 19th century, the international carpet trade developed an increasing interest in India. The years succeeding World War I witnessed a significant growth in exports to the United States, initially of coarser-quality rugs featuring the French Aubusson pattern (a formal floral design) and Chinese-inspired motifs. Beginning in the 1970s the Indian rug industry, responding to an international demand for Persian-design rugs, returned to its historic Persian weaving tradition by developing and producing increasingly finer qualities of rugs. Today, the Indian weaver not only creates works which rival their Persian counterparts but which also reveal a creative ingenuity of their own. At present, India is one of the primary sources for both pile and flat-woven rugs available in an impressive range of qualities, designs, colorations, and sizes. Indeed, Indian weavers have demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt to ever-changing Western decorative tastes while recreating Persian rug designs at increasingly higher quality standards. As in the past, Indian weaving production is currently organized on a cottage industry basis, and the vast majority of pile rugs and flat weaves are crafted in villages throughout the Mirzapur/Bhadohi region while smaller centers are located in Jaipur, Gwalior, Kashmir, Agra, and Amritsar. Aubusson-patterned rugs are now a minor factor in the export market, as Persian-design carpets constitute the predominant category of Indian pile rugs woven today. Thanks to the weavers' expert understanding and execution of design, coloration, and knot density, these rugs are often considered to best approximate the look, texture, and feel of their Iranian-made counterparts. Kashan, Tabriz, Kerman, Sarouk, and Bijar are among the many popular Persian patterns that have inspired faithful recreations and innovative adaptations. The Indian weaver has mastered the rendition of these patterns in traditional Persian-style hues (e.g., dark reds and blues) and in contemporary colorations, including jewel tones and pastels, attuned to the very latest in home furnishings fashion trends. Moreover, their rugs are produced in an impressive range of qualities averaging from approximately 85 to 150 knots per square inch. Some Indian weavers' dexterity is such that they are even able to produce carpets with over 300 knots per square inch. The woolen yarns used are generally blends of Indian and imported New Zealand wool which together provide the carpet with a naturally lustrous appearance. Additionally, a small number of all-silk carpets featuring about 400 knots per square inch continue to be produced in Kashmir.

The expertise of India's weavers extends beyond that of producing pile carpets. Indeed, the country is equally renowned for its production of flat weaves, notably dhurries and chainstitch rugs whose techniques are indigenous to its culture and date back possibly several thousands of years. These handcrafted flat weaves blend in with a variety of contemporary and traditional settings while offering an excellent and affordable purchasing opportunity that may be particularly appealing to the first-time buyer.

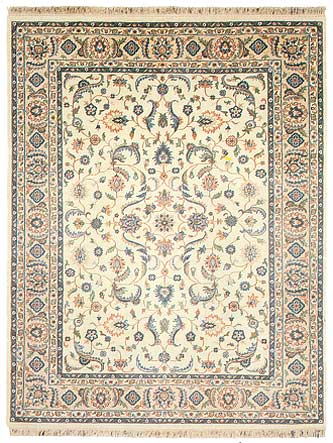

Most popular in the last decade have been wool dhurries, now mainly characterized by floral designs in an array of fashionable colorations including pastels and more vibrant hues. Also available, although in lesser quantity, are cotton dhurries displaying bold geometric patterns. Chainstitch or crewel-embroidered rugs - chiefly produced in and traditionally indigenous to Kashmir - have recently experienced a tremendous resurgence in popularity thanks to their exquisitely detailed floral patterns, often European-inspired, executed in a full range of contemporary colorations. India is a world leader in Oriental rug exports thanks to its tremendous production capacity and to its weavers' dexterity, versatility, and willingness to constantly experiment with color and design combinations in an attempt to be responsive to American consumer demand. India offers a complete range of pile and flat-woven rugs in a wide range of qualities, styles, colors, and sizes. These handcrafted floor coverings are suitable for a broad spectrum of decorative specifications in residential and commercial settings alike. CHINA Chinese carpets were first woven centuries ago by nomadic tribes in the Sinkiang and Ninghsia regions of western China where they were used for both decorative and functional purposes. In the early to mid-19th century, this simple craft began to flourish on a much larger scale at the Imperial Court of Beijing. Particularly instrumental in developing the art was the patronage of Ch'ien Lung, Chia Ch'ing, and Tao Kuang, three rulers of the Ch'ing Dynasty (1644-1912). During the mid-to-late 19th century, China's entire carpet production was destined for local consumption, being sold commercially to the native noble and upper classes. Western awareness of Chinese weavings increased significantly during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 when many palaces and residences were looted and the spoils of war were sent abroad. Chinese carpets first won official recognition at the 1903 Saint Louis International Exhibition where an entry was awarded first prize. With Western interest now kindled, substantial efforts were made to transform a cottage handicraft into a major industry in the Beijing/Tianjin area of northeastern China. In the 1920s, so-called Peking- and Tiensin-style rugs were produced according to American importers' specifications and were "all the rage" in the United States. Following President Richard Nixon's memorable trips to China in 1971 and 1972, which resulted in the reestablishment of trade between the United States and China, Chinese carpets reemerged in the United States in 1973. They have since become a major force in the home furnishings market due to their tremendous versatility in type, style, and color, and executed with high quality control standards. Equally important has been the Chinese weavers' expertise and willingness to adapt designs and colorations to American decorative trends. Most carpets are still woven in the northeastern provinces of China with the balance originating from the western and southern regions. Weaving is performed in factories scattered in cities and throughout the countryside. Rug production is essentially made up of autonomous provincial enterprises or cooperatives, each competing for a share of the market. The rugs are warehoused for export in the principal cities or ports of the producing provinces. Notable among the producing cities are Beijing, Tianjin, Qingdao, Shanghai, Dalian, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Baoding. The factories have from a few to several hundred looms, and the manufacturing process is closely supervised for quality control. While many of the looms are still built of wood, most new ones are built of steel. As they are so well built and stout, whether of wood or steel, crooked pieces are seldom produced. The carpets are woven of excellent quality indigenous wool featuring durable and resilient yarn or with a blend of native and imported wool. Today's consumer has a wealth of patterns and colors to choose from both in pile and flat-woven rugs. The most popular design categories for pile rugs are Peking, floral, esthetic, and Sino-Persian. Peking rugs, stylistically the most indigenous to Chinese culture, generally feature a central medallion on an open or covered field of traditional and often stylized motifs and symbols, such as animals, flowers, clouds, and vases, framed by a simple, wide border. Equally in demand are floral rugs often characterized by an all-over pattern or by asymmetrically placed floral sprays. The popular Art Deco style floral carpets, based on the "Tientsin-style" rugs of the 1920s, generally feature an asymmetrical floral pattern sometimes with objects such as birds and pagodas, and wide solid-colored borders. Esthetic rugs inspired by the floral patterns of French Savonnerie and Aubusson carpets are generally characterized by a large central medallion and an open field with surrounding designs.

Peking, floral, and esthetic rugs' colorations are keyed to the very latest American decorative trends and range from pastels to the more vibrant jewel tones. These three rugs styles - usually carved or incised to produce depth and shading - are woven in qualities ranging from 70 to 120 lines and averaging 90 lines. This line count system is unique to China, and a 90-line rug, for instance, means that it has 90 knots in one linear foot both across the width and length of the rug and contains approximately 56 knots per square inch (90 knots times 90 knots divided by 144 inches per square foot equals 56 knots per square inch). Undoubtedly, the most talked about category of Chinese carpets woven today is the Sino-Persian. These carpets rival their Persian-design counterparts originating in Iran, India, Rumania, and Pakistan. They are produced in qualities ranging from 120 to 300 lines, with most pieces averaging 200 lines (approximately 278 knots per square inch). Sino-Persian rugs are based on Iran's most celebrated designs, namely Kashan, Lavar Kerman, Sarouk, Tabriz, and Isfahan, and are executed in a broad array of both traditional Persian (e.g., dark reds and blues) and contemporary hues. After receiving hundreds of Persian designs from importers around the world, Chinese designers have now developed the ability to "rework" their vast repertoire of design elements into an infinite number of new designs rivaling Iran itself. A smaller but nonetheless important segment of Chinese pile rug types includes contemporary-design pieces - displaying a broad spectrum of free-form patterns - and antique-style rugs that are attractive recreations of vintage Peking-style rugs often woven with vegetable-dyed wool. Also available are limited quantities of silk carpets, generally in smaller sizes, containing up to 625 knots per square inch. Virtually unique to China is the production of wool pile rugs in odd shapes. Indeed, rounds, ovals, squares, and hexagons are available in a broad range of styles and colors. They are particularly well suited in defining a room's particular angle.

In the last decade Chinese flat weaves, namely kilims and needlepoints, have made tremendous inroads into the marketplace. Chinese kilims offer an excellent variety of floral and geometric patterns in traditional and fashion-oriented colors and in a wide range of sizes including standard room sizes which are often difficult to find in other types of flat weaves. Needlepoint rugs have recently been reintroduced to the American market and are enjoying the same success they had had during the 1920s and 1930s. Hand-embroidered in wool, these floor coverings exquisitely recreate the look of 18th and 19th century English and French needlepoints in a vast spectrum of colors. Noteworthy as well are tufted carpets (also referred to as full-cuts, gun-tufted, or latex-backed carpets) which haven been produced in China for several decades. Because these carpets are not woven on a warp and weft foundation they do not technically qualify as Oriental rugs. The pile of these carpets is created with a hand-held tufting gun which loops the yarn through a canvas type backing. The back of the loops is then covered with latex to prevent the tufts from being pulled out. The loops on the face are then sheared to create a cut pile very similar to the pile of an Oriental rug, and the back is covered with a cloth to protect the latex foundation. Since the same wool, washing, and carving techniques are used to produce these carpets as used in handknotted carpets, they have a very similar appearance from the face. While these carpets represent excellent value, you should be aware that they are not handwoven Oriental carpets. China offers the consumer one of the broadest varieties of design styles including Chinese, Persian, European, and contemporary to choose from. Equally appealing are the rugs' decoratively attuned colorations as well as the variety of construction types such as pile, kilim, and needlepoint. Having established an enviable reputation in decorative home furnishings, it is no wonder that today China is a leading exporter of Oriental carpets to the United States. PAKISTAN The art of carpet weaving originated in the Indian subcontinent under the reign of Akbar the Great (1542-1605). During that period, Persian weavers were brought to Lahore where several carpet factories were established. In the years that ensued, weaving in this region developed at an impressive pace. Following the partition of India in 1947, Pakistan became a geopolitical entity where Moslem weavers from India, and Turkoman craftsmen from the north, were attracted to the large weaving centers located in and around the cities of Lahore and Karachi. With the help of government subsidies, the carpet industry began to flourish in the 1960s and has since become one of the most significant sources of export revenue for this country.

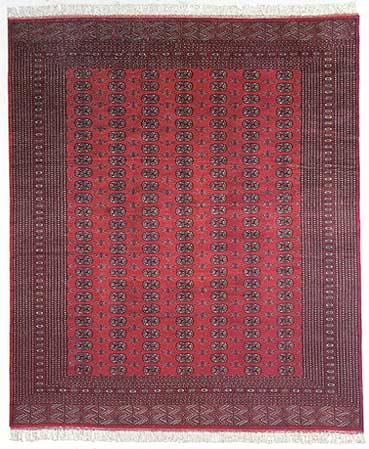

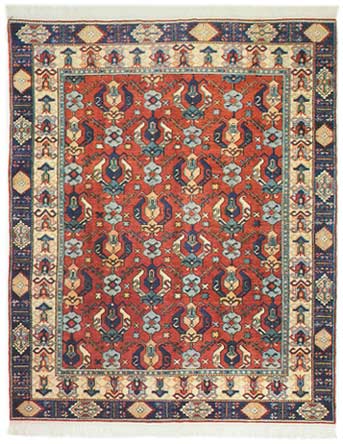

In contemporary Pakistan, carpet weaving has remained mainly a cottage industry with the great majority of pieces manufactured in individual dwellings which may contain several looms. Today, rugs are woven with high-quality blends of indigenous and imported wool. Approximately 70% of the weaving is done within a 400-mile radius of Lahore, the capital of the Punjab province. Karachi, the capital of the Sind province, represents some 20% of the total output. The areas around the cities of Quetta and Peshawar generate the remaining 10%. Until the 1970s, Pakistan had predominantly woven Bokkaras characterized by a repetitive octagonal or gul motif which is based on a traditional Central Asian Turkoman design. Today Bokkaras still account for a significant portion of total production and are available in two styles, Mori and Jaldar. Mori Bokkaras feature the traditional gul motif and come in a broad array of colors - including traditional hues (e.g., reds, rusts, and ivories), pastels, and fashion shades (e.g., peaches, corals, greys). More recent has been the development of Jaldar Bokkaras generally displaying geometric, contemporary-style designs as well as motifs based on nomadic Caucasian sources. Colors are mainly contemporary, including pastels and jewel tones as well as black. Mori Bokkaras are generally woven in qualities of 200 to 242 knots per square inch while Jaldar Bokkaras range from 162 to 200 knots per square inch. Bokkaras come in a full assortment of sizes ranging from one-foot squares to room sizes and runners.

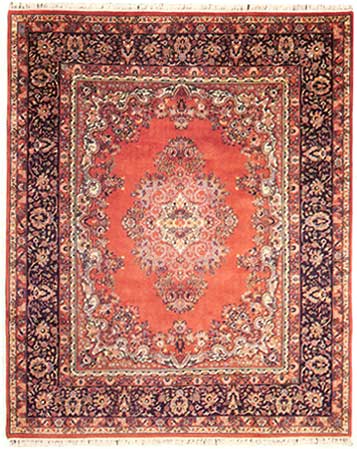

In the last decade, higher-quality Persian-design carpets featuring colorations attuned to American fashion have become the predominant type of Oriental carpets available in Pakistan. Here, the weavers possess an almost intuitive sense in executing the designs of their Iranian neighbors thanks to their historical association with Persian weaving techniques and to their Islamic cultural and religious background. By far, the most readily available quality of Pakistani Persian-design carpets today is the so-called 16/18 which is roughly equivalent to 288 knots per square inch. Pakistani 16/18 weavers generally concentrate on reproducing the more intricate Persian patterns - namely Kashan, Tabriz, Nain, and Isfahan - which require a greater number of knots. These designs are colored to suit all tastes including the traditional Persian reds and navies, in addition to pastels and the very latest designer hues. It's not unusual for these fine carpets to contain as many as 20 different colors. In addition, the 16/18s' low pile height enhances the crispness of the designs and their tight' 'handle" or feel approximates that of their Persian counterparts. Persian-design carpets are also found in other qualities ranging from about 195 to 324 knots per square inch, but the latter knot count quality only exists in smaller-sized rugs of 4' x 6' and below. Pakistan deserves careful consideration as its very strong production capacity is geared to specific American decorative requirements. The broad range in colors and patterns, as well as the availability of higher-end Persian-style carpets, provides ample choices for today's consumer. TURKEY Until Persian rugs were exported in the 17th century, Turkish weavings were the only Oriental floor coverings known to Europe and thus the terms "Turkey carpets" and "Oriental carpets" were virtually interchangeable. Turkey's rug-weaving industry dates back to the llth century and was developed successively by the Seljuk (llth - 13th centuries) and Ottoman (c. 1300 -1922) dynasties and by the modem Turkish republic. The Oriental rugs currently being produced in Turkey have the historic character of their antique counterparts in patterns and colors geared to today's decorative tastes. As in Iran, rug weaving in Turkey is an intrinsic part of its culture and is practiced in villages throughout the country. A substantial portion of the production is destined for domestic and local tourist consumption rather than for export. Thus, much of the demand for these weavings - including pile rugs and flat weaves, saddle and grain bags, and silk pieces - comes from collectors and consumers looking for something that is both different and distinctive. Indeed, it is often said that Turkey's appeal emanates from its carpets' tribal, primitive character. Of special interest today is the renaissance of traditional weaving techniques, namely that of using vegetable dyes and handspun wool (produced from both domestic and imported wool) in areas around Izmir, Canakkale, Konya, Kayseri, Oushak, Hercke, Diyarbakir, Malatya, Kars, and Erzurum. Originally initiated in 1982 by the government-administered project DOBAG (Natural Dye Research and Development Project), the resurgence of this weaving art has spread throughout Turkey, making it a major producer of Oriental carpets whose wool is both handspun and vegetable-dyed. This ancient, time-consuming, and delicate process of using vegetable dyes, as compared to chemical dyes, imparts the wool with a very unique patina. For instance, the darker reds and blues have a very characteristic vibrancy and the light hues exude a complex transparency. Among the plants used to extract dyes are madder and indigo.

Equally important has been the recreation of authentic old Ottoman patterns as well as those from other countries and regions including Iran, Azerbaijan, the Caucasus, East Turkestan, and Transylvania. These adapted patterns, though not originating from the villages or areas where they are woven, are nonetheless integrated into the Turkish weavers' design library thereby bestowing a charm and uniqueness of their own. The designs - generally intricate interplays of geometric and curvilinear floral motifs - are woven in an array of colors ranging from full-bodied reds, blues, teals, greens, and greys, to the lighter peach and ivory tones. Carving and incising is done to highlight designs in many of the pile rugs. Among the popular carpet types available today are all-wool Basmakcis that feature geometric patterns inspired by Caucasian and traditional Turkish designs. Burdurs are also popular and are characterized by the angular Persian Heriz design woven in both traditional and contemporary colorations. Hereke rugs, renowned both in their wool and silk varieties, have repeating intertwining floral elements often incorporating the mihrab or prayer niche. The last decade has witnessed the growing popularity of kilims mainly featuring a broad range of geometric patterns characteristic of Anatolia (a generic term referring to the high plains of Central Turkey). They are also available in the Karabagh variety and bear more Western-looking stylized floral motifs reminiscent of Bessarabians. Although produced throughout Turkey, most of the kilims produced originate from the Oushak and Denizli areas. The organized production of Oriental carpets in Turkey is one of the most exciting developments in the industry. Indeed, the renaissance in the use of vegetable dyes and handspun wool, and the creative renderings of designs both native and foreign has inspired the production of carpets bearing a unique, handcrafted character, some of which are destined to be the "antiques of tomorrow." THE CAUCASUS (Caucasian) The Caucasus region - now comprised of several Soviet states - belonged to Persia until the early nineteenth century and is the home of diverse tribes of many separate languages, as well as two main religions - Christianity and Islam. The rugs produced here reflect the unsophisticated character of the people who live in this rugged mountainous area - bold & vigorous designs that feature bright colors and strong contrast - the overall effect being geometric, even primitive and of relatively modest proportions but remarkably uniform in style. As such no regulated weaving industry exists, and collector pieces date back only as far as the last half of the eighteenth century.

TIBET/NEPAL Although historical references pointing to the specific origins of Tibetan rugs are unclear, it is believed that carpet weaving in this Himalayan region is part of an age-old tradition practiced primarily for use in the home. Following China's suppression of Tibetan nationalism in 1959, thousands of Tibetans fled Tibet and settled in neighboring countries including Nepal. Shortly thereafter, carpet production began in Tibetan refugee camps, mainly situated in Nepal's Kathmandu (Katmandu) valley. By the mid-1970s, many carpets woven by Tibetans in exile were being exported to Europe. During the 1980s, Tibetan/Nepalese rugs have received increasing attention from the United States decorative market and exports to this country have steadily increased. The primitive, handcrafted look of these carpets, characterized by highly stylized patterns and tastefully orchestrated color schemes, has great appeal for the American consumer.

Originally produced as mats, door covers, saddle rugs, bed covers, and pillar rugs (made to fit around Buddhist temple columns), traditional Tibetan weavings generally reflect the significance of Buddhist religion in Tibetan culture and art. Various Chinese design elements were also adopted and transformed by the Tibetans as evidenced by the common use of the phoenix, dragon, and lotus symbols in traditional Tibetan carpets. Today, design schemes featured in Tibetan/Nepalese carpets (that is carpets woven by Tibetan refugees in Nepal) range from Westernized adaptations of traditional Tibetan motifs (e.g., branching floral designs and snow lions) to a vast medley of foreign and contemporary free-form patterns. Among the patterns adapted from non-Tibetan cultures are traditional Persian, Turkish, French, Bessarabian, and American southwest Indian. The contemporary-design rugs feature bold geometrics on open fields and adaptations of Art Deco designs. Whatever their ethnic origins, Tibetan/Nepalese patterns bespeak a compelling simplicity that is enhanced by a color spectrum spanning from the rich reds and blues to the softer lavenders and greys. In some cases, these hues are obtained through the use of vegetable dyes. Generally, the yarn used in Tibetan/Nepalese carpets is carded and spun by hand. This gives the face of these carpets a wonderful depth and richness achieved through the subtle variation of color and texture. Some rugs are woven exclusively with Tibetan wool which is characteristically flexible, strong, lustrous, and springy. The majority of the rugs woven are a blend of Tibetan and imported wool. Knot counts vary from 30 to 100 knots per square inch with the majority approximating 48 knots per square inch. The looms used today are larger than their native predecessors in order to meet the export demand for room-sized carpets. Tibetan weaving features a unique and ancient knotting technique which utilizes the "axis rod" (warp divider) and "gauge rod" (needle), tools not employed in other rug weaving countries. Tibetan/Nepalese carpets are increasingly coming into their own in the United States, stirring considerable excitement among American buyers. Indeed, they impart the rustic charm, characteristic of their traditional Tibetan counterparts, while featuring fashion-oriented colors and designs available in a full range of sizes. These bold, eclectic patterns and colorations heightened by a rich texture reveal a primitive sophistication unique to these carpets. SAMARKAND (Mongolia) Produced as far north and east as Mongolia, the rugs that fall into the category of Samarkand - named for the oldest-known city in Asia - incorporate features of both the Persian and Chinese rug, with design elements which include: circular-shaped medallions (used in various configurations) as well as flowers, trefoil leaves and pomegranates, but instead of a predominantly red background color, such as in Turkoman rugs, these rugs feature a lighter, brighter, color palette of soft blue, gray, and tan fields, with accents and border elements of yellows, blues, and bright reds.

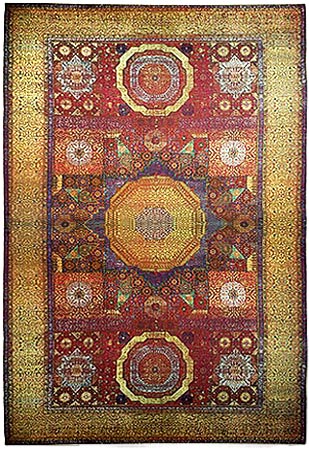

Variations in design range from a single center medallion, to portions of the medallion woven into each corner surrounded by a border usually wider than on Chinese rugs and that may include a number of guard stripes. Thematic elements may include a pomegranate tree growing out of a vase on a singular color field, or a ground populated with Chinese butterflies, cranes, dragon(s), fish, or an endless knot motif. The rugs that fall into this category, named more for the style of the rug rather than it's place of origin, are typically hand woven of wool or silk using a Persian knot. EGYPT A Jewel Worthy of Royalty - The creation of the brilliant many-faceted 16th Century silk carpet (below), almost eighteen feet in length, and with a knot density of over 200 knots per square inch, and once the property of the House of Hapsburg, has been, over time, whimsically associated with a charming fairy tale. Once Upon A Time ... as the story goes, a thief was running off with a King's largest, most precious diamond when suddenly, the thief dropped the stone, and the diamond fell on a rock - shattering into pieces. Subsequently, the grieving monarch ordered that a carpet be woven to emulate the appearance of a landscape strewn with the fragments of his favorite stone.

Whatever it's inspiration, experts consider this Mamluk medallion carpet, woven in Cairo of finely-knotted silk in luminescent and shimmering colors, a supreme achievement of the art of Oriental rugmaking - and one of the world's finest carpets, and certainly one of a kind. Introduction |

The Illustrated Rug - Part 1 |

The Illustrated Rug - Part 3 |

Rugs of Afghanistan |